What Is Celiac Disease Pathology?

Celiac disease pathology focuses on the structural and functional changes in tissues caused by this autoimmune disorder. Celiac disease occurs when the body mounts an immune response to gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. This immune response primarily damages the small intestine, particularly the villi—tiny finger-like projections responsible for nutrient absorption. The disease’s pathology encompasses the mechanisms and tissue-level alterations that lead to nutrient malabsorption and systemic complications.

Research reveals that individuals with certain genetic markers, particularly HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8, are more susceptible to developing celiac disease. These genetic factors, combined with environmental triggers like gluten, set the stage for the pathological changes seen in this condition. Understanding celiac disease pathology is essential for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and preventing further complications. For a more comprehensive overview of the basics, you can explore Celiac Disease Basics.

The Role of Gluten in Celiac Disease Pathology

How Gluten Triggers an Autoimmune Response

The pathology of celiac disease begins with gluten consumption. Gluten proteins, particularly gliadin, are resistant to complete digestion, leaving behind peptides that the body recognizes as harmful. In genetically predisposed individuals, these peptides interact with tissue transglutaminase (tTG) in the small intestine. This interaction creates a modified form of gliadin that activates the immune system.

The immune response involves T-cells that release inflammatory cytokines, damaging the intestinal lining. Over time, this inflammation leads to villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia—hallmark features of celiac disease pathology. The damage reduces the intestine’s ability to absorb nutrients, resulting in deficiencies and systemic effects.

Impact on the Small Intestinal Lining

The small intestine’s lining is the primary target of gluten-induced damage. Normally, the villi increase the surface area for nutrient absorption. However, in celiac disease, these villi become flattened or destroyed, a condition known as villous atrophy. Alongside villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia occurs, where the crypts, or pits between the villi, enlarge as the intestine tries to repair itself. These combined effects disrupt nutrient absorption and lead to conditions like iron-deficiency anemia, weight loss, and osteoporosis. To further understand gluten’s impact, explore Gluten and Inflammation.

The Immunological Mechanisms Behind Celiac Disease

Celiac disease pathology is driven by a complex interplay of immune system components. When gluten peptides reach the small intestine, they undergo modification by tissue transglutaminase. This modification enhances their ability to bind to HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 molecules on antigen-presenting cells. These complexes activate T-cells, which then release pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Autoantibodies and Systemic Effects

The immune system produces autoantibodies, such as anti-tTG and anti-endomysial antibodies, which contribute to tissue damage. These autoantibodies are key diagnostic markers for celiac disease and can be detected through blood tests. Additionally, systemic effects of the immune response can manifest as neurological symptoms, skin conditions like dermatitis herpetiformis, and complications such as infertility or miscarriage.

To better understand the genetic predisposition associated with the disease, visit Understanding the Celiac Gene.

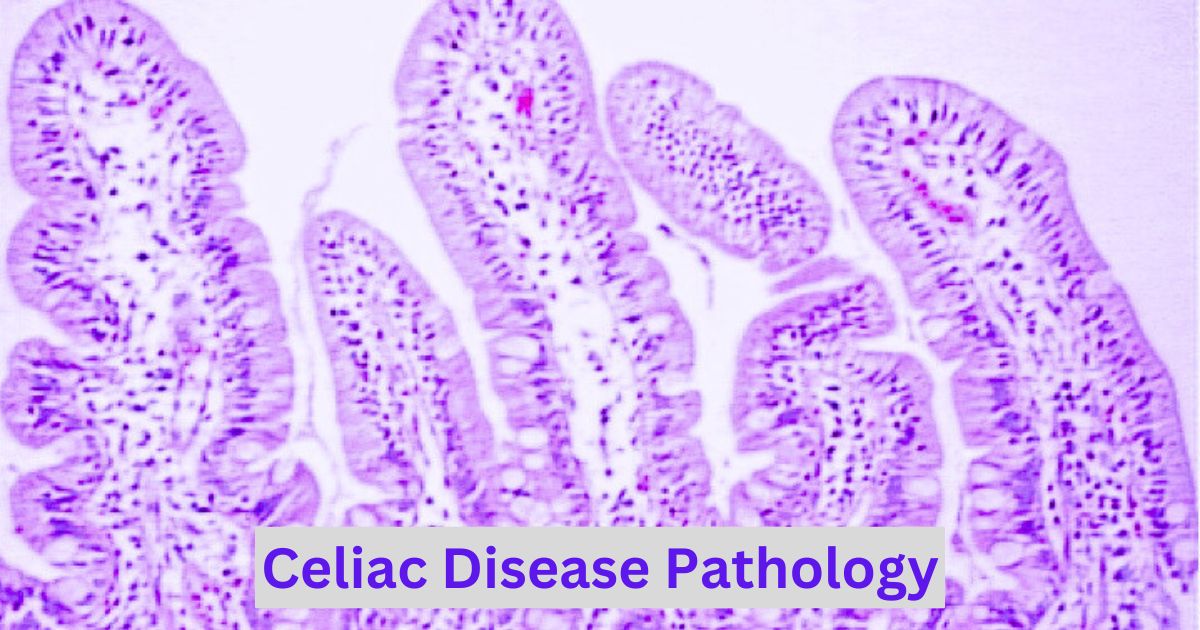

Histopathological Changes in Celiac Disease

Villous Atrophy and Crypt Hyperplasia

Villous atrophy is a defining feature of celiac disease pathology. It represents the destruction of the villi, leading to a smooth intestinal surface with significantly reduced absorption capacity. Crypt hyperplasia occurs simultaneously, marked by the enlargement of the pits between the villi, as the body attempts to regenerate damaged tissue.

Increased Intraepithelial Lymphocytes

Another critical pathological change is an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). These immune cells infiltrate the epithelial lining of the small intestine in response to gluten exposure. Their presence reflects ongoing inflammation and immune activation.

These histological changes are evaluated through intestinal biopsy, the gold standard for celiac disease diagnosis. A biopsy not only confirms the presence of these abnormalities but also helps distinguish celiac disease from other conditions like Crohn’s disease or food intolerances. To learn more about the diagnostic process, read Celiac Disease Diagnosis.

For further scientific details on the pathology of celiac disease, the National Library of Medicine provides an excellent resource: NIH Celiac Disease Pathology Overview.

Symptoms Linked to Celiac Disease Pathology

Celiac disease pathology leads to a variety of symptoms, ranging from mild digestive discomfort to severe systemic issues. The symptoms can be divided into two categories: digestive and non-digestive, reflecting the wide-reaching impact of this autoimmune disorder.

Digestive Symptoms

Digestive symptoms are often the first signs of celiac disease and are directly linked to damage in the small intestine. These symptoms include:

- Chronic diarrhea or constipation

- Bloating and gas

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pale, foul-smelling stools (steatorrhea)

Non-Digestive Symptoms

Non-digestive symptoms result from nutrient deficiencies caused by impaired absorption. These symptoms may include:

- Fatigue and weakness due to iron-deficiency anemia

- Osteoporosis or bone pain from calcium and vitamin D deficiencies

- Neurological issues like tingling in the hands and feet

- Skin conditions such as dermatitis herpetiformis

- Delayed growth and puberty in children

Understanding these symptoms is crucial for early diagnosis. For more on identifying early warning signs, explore Symptoms of Celiac Disease.

Diagnostic Pathology in Celiac Disease

Accurate diagnosis of celiac disease involves identifying both clinical symptoms and pathological changes in the small intestine. The diagnostic process typically includes blood tests, genetic testing, and intestinal biopsies.

Blood Tests and Biomarkers

Blood tests play a critical role in diagnosing celiac disease by detecting specific antibodies, including:

- Anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibodies

- Anti-endomysial antibodies (EMA)

- Deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP) antibodies

The presence of these antibodies indicates an immune response to gluten. These tests are particularly useful in the early stages of diagnosis.

The Role of Intestinal Biopsies

A biopsy of the small intestine is the gold standard for confirming celiac disease. During this procedure, a small tissue sample is taken from the duodenum and examined for histopathological changes such as villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes. This confirms the diagnosis and helps rule out other conditions, such as Crohn’s disease or irritable bowel syndrome.

For additional insights into diagnostic procedures, read Celiac Disease Diagnosis.

Complications of Untreated Celiac Disease Pathology

When celiac disease remains undiagnosed or untreated, its pathology progresses, leading to severe complications that can impact overall health.

Long-Term Damage and Associated Conditions

The cumulative damage to the small intestine can result in:

- Malnutrition: Severe deficiencies in essential nutrients due to impaired absorption.

- Osteoporosis: Weak and brittle bones caused by chronic calcium and vitamin D deficiency.

- Infertility: Hormonal imbalances and nutritional deficiencies can impair reproductive health.

- Neurological Disorders: Conditions like ataxia and neuropathy result from deficiencies in vitamin B12 and other nutrients.

Additionally, untreated celiac disease increases the risk of certain cancers, particularly small bowel adenocarcinoma and lymphoma.

Understanding the complications highlights the importance of early diagnosis and management. You can learn more about the long-term effects of celiac disease by visiting Exploring the Causes of Celiac Disease.

How to Manage and Treat Celiac Disease Pathology

The cornerstone of managing celiac disease is adhering to a strict gluten-free diet. Eliminating gluten allows the intestinal lining to heal and prevents further damage.

Key Dietary Adjustments

- Avoid Gluten: Eliminate all forms of wheat, barley, rye, and their derivatives from your diet.

- Check Labels: Many processed foods and condiments contain hidden gluten. Learn to read food labels carefully.

- Gluten-Free Substitutes: Incorporate alternatives like rice, quinoa, buckwheat, and certified gluten-free oats.

Additional Treatments for Severe Cases

In cases of advanced celiac disease or refractory celiac disease, additional interventions may be required, such as:

- Vitamin and mineral supplementation to address deficiencies.

- Medications like corticosteroids to control severe inflammation.

- Regular monitoring for complications through follow-up medical checkups.

For a comprehensive guide to living gluten-free, explore Living Gluten-Free.

Summary

Celiac disease pathology encompasses the complex immune and histological changes triggered by gluten in genetically predisposed individuals. Understanding these processes is key to effective diagnosis, management, and prevention of complications. A gluten-free diet remains the cornerstone of treatment, but ongoing research promises new therapies that may further improve outcomes. By adhering to dietary recommendations, supporting gut health, and staying informed about advancements, individuals with celiac disease can lead healthier lives.

FAQs

1. What is celiac disease pathology?

Celiac disease pathology refers to the structural and functional changes in tissues caused by the body’s immune response to gluten.

2. How does gluten affect the small intestine in celiac disease?

Gluten triggers an immune response that damages the intestinal lining, leading to villous atrophy and impaired nutrient absorption.

3. Can celiac disease be reversed with treatment?

While the damage caused by celiac disease can partially heal with a strict gluten-free diet, it cannot be fully reversed in advanced stages.

4. What are the most common symptoms of celiac disease pathology?

Symptoms include chronic diarrhea, bloating, fatigue, iron-deficiency anemia, and neurological issues.

5. How is celiac disease diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves blood tests for antibodies, genetic testing for HLA markers, and intestinal biopsy to confirm tissue damage.

6. Are there complications of untreated celiac disease?

Yes, untreated celiac disease can lead to malnutrition, osteoporosis, infertility, and increased risk of certain cancers.

7. What are some gluten-free alternatives to common foods?

Alternatives include gluten-free bread, rice pasta, quinoa, millet, and certified gluten-free oats.